Samuel Rutherford on Divine Providence

“When the Lord’s blessed will bloweth across your desires, it is best, in humility, to strike sail to him, and to be willing to be led any way our Lord pleaseth” (p78).

If you were hoping for a precise systematic exposition of the often confusing, sometimes unnerving and always difficult doctrine of God’s providence then you are in the wrong place. For my devotional reading I have been working through Samuel Rutherford’s Letters (Banner of Truth, 1973) and as I have made my way through them it has become apparent that Rutherford was more than qualified to speak about God’s providence and wrestling with it.

If you were hoping for a precise systematic exposition of the often confusing, sometimes unnerving and always difficult doctrine of God’s providence then you are in the wrong place. For my devotional reading I have been working through Samuel Rutherford’s Letters (Banner of Truth, 1973) and as I have made my way through them it has become apparent that Rutherford was more than qualified to speak about God’s providence and wrestling with it.

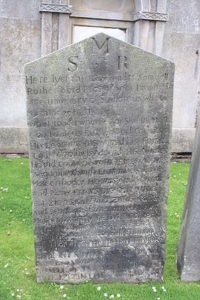

At the age of 27, recently armed with an MA in divinity, Rutherford settled in Anwoth, a small rural town in the south of Scotland, and for the next 9 years he served as a devoted pastor in that dispersed community. Rutherford was, before anything else, a wonderfully gifted and genuinely committed pastor who loved God’s people, or kirk. The energy he poured into the people of Anwoth did not go unnoticed; there stands to this day a massive obelisk which was erected in his honour in the 19th century.

However Rutherford’s road was not a smooth one as he was forcibly relocated to Aberdeen in 1636 as a result of his Calvinistic theology and non-conformity with the Arminian theology, which was becoming increasingly prevalent. Despite Charles I claiming Protestant allegiance, his interest was lacking at local level; religious turmoil, which frequently stung the Puritans, reigned alongside the monarch. The long and short of it is that Rutherford was torn from his sheep in Anwoth. The agony of being away from those with whom he had shared rich Christian fellowship is evident in the letters he wrote from Aberdeen, almost all of which were penned to provide pastoral guidance and Christian counsel. But another thing that is hard to ignore is Rutherford’s grappling with God’s providence. Why had he been sent to Aberdeen? Why did God allow the Arminians to drive him from his local parish in Anwoth, abandoning his congregation to the proverbial wolves?

Rutherford’s grief at having his ministry in Anwoth derailed came as a probing challenge to his faith in Christ. His struggles drove him back to Christ and were most probably the cause for one of his favourite expressions, ‘the sweet cross of Christ’. Suffering did not cause him to question God’s love but rather to query God’s plan. And so in a letter, addressed to Marion M'Naught (p16), who was Rutherford’s most contacted correspondent, he challenged her, “employ all of your endeavours for establishing an honest ministry in your town, now when you have so few to speak a good word for you." Marion had written to Rutherford out of desperation at her situation, being one of very few Christians in the town she called home. Rutherford’s response was simply that she was to make use of her trying circumstances and difficulties in witnessing to Christ, glorifying him in her life and trusting him that she was there because God intended her to be.

This view undergirds much of Rutherford’s correspondence. So providence for Rutherford was not the cold, calculated doctrine that says God is in control and moving us around like chess pieces but the warm, faith-enriching truth that God is at work guiding us back to him and forcing us to look around at where we find ourselves and ask how we might glorify God in the situation he has placed us.

The above understanding that Rutherford presents is nowhere as clearly evinced, in my own reading so far, as in his letter to John Stuart (p76). John Stuart had run into serious difficulties with business and was delayed from getting to New England. Rutherford assured him that the events were not some strange “dumb Providence” (p77). Stuart’s business had suffered significantly and he was despondent but Rutherford pointed him to God’s loving kindness and its immense depth. Rutherford goes on, “I hope that you have been asking what the Lord meaneth, and what further may be his will, in reference to your return”. Rutherford encouraged Stuart that despite the dark side of providence God had a better side which he will show to those who are courageous.

When Rutherford utilises Romans 8:28, too often quoted without much sensitivity to those in turmoil, we can agree that God does work for the good of those who love him. “Hence, I infer that losses, disappointments, ill-tongues, loss of friends, houses or country, are God’s workmen” set to work for the believer’s good (p78). Despite the hardships that befall us, Rutherford reminds us that in what seems like unfatherly hardship God is not being unpleasant towards us. God brings us to the place where we must deny ourselves, to be as if we had no will at all, and sell ourselves over to God’s sovereign work in the world, his providence, in free disposition of our wants and longings. Rutherford concluded this point in his letter to John Stuart exhorting the reader to makes use of God’s will, which Rutherford believed was “true holiness, and your ease and peace”.

Why does any of this matter; where does it intersect with us and our own lives? The point to emphasise is this: we are not called to trust glibly in God’s providence, affirming his control over all matters blindly; from Rutherford’s experienced pen we learn that God’s providence invites us to put aside our desires and hopes, and allow ourselves to be swept along with God, dedicating ourselves in faith to his desires for this world.