Allegory in Our Reading of Exodus 3

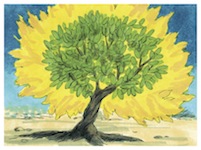

Rudolf Otto famously wrote, ‘Mysterium tremendum et fascinans’, to explain the human experience of the divine, the Holy. Literally it means something like, ‘fearful and fascinating Mystery’. Otto’s idea of the Holy was that we are drawn toward its magnificence in wonder, yet repelled by its awesomeness. R.W.L. Moberly suggests that a fire that burns without consuming is perhaps the prime symbol for God because it attracts (by its vivid movement) and deters (by its heat). But is this the intention of Moses’ first theophany, in Exodus 3? How are we meant to understand this great sight, a bush that burns and is not consumed (3:2-3)?

Rudolf Otto famously wrote, ‘Mysterium tremendum et fascinans’, to explain the human experience of the divine, the Holy. Literally it means something like, ‘fearful and fascinating Mystery’. Otto’s idea of the Holy was that we are drawn toward its magnificence in wonder, yet repelled by its awesomeness. R.W.L. Moberly suggests that a fire that burns without consuming is perhaps the prime symbol for God because it attracts (by its vivid movement) and deters (by its heat). But is this the intention of Moses’ first theophany, in Exodus 3? How are we meant to understand this great sight, a bush that burns and is not consumed (3:2-3)?

I ask the question because I recently preached on Exodus 3 and engaged with the commentators and listened to a few sermons. Many interpretations – even if only in passing – sound like Rudolf Otto. The fire that does not consume is interpreted as a picture of Yahweh’s presence amongst his people; despite his transcendent holiness he comes near to the Hebrews in the exodus event. Bruce Waltke says in his Old Testament theology: the image of fire inhabiting that fit for kindling is a foreshadowing of God amongst the Hebrews (p363). There is no doubt that fire is linked with God’s presence in Exodus; the Hebrews are lead by a pillar of fire and cloud (13:22), fire symbolises God’s presence at Sinai (19:18), and God’s glory descends as cloud and fire onto the completed tabernacle (40:34-38). But can we conclude from this that the unaffected burning bush depicts the holy Yahweh dwelling amongst a people his nature should consume?

Alan Cole thinks the fire might signify the “purificatory, as well as destructive” properties of God’s presence. That would come closer to my understanding of God’s holiness; which is not mere otherness and transcendence but an outwardly flowing attribute that creates holiness, destroys evil. As Jonathan Edwards wrote, 'It is fit, as there is an infinite fountain of holiness, moral excellence and beauty, so it should flow out in communicated holiness’ (quoted by John Webster in Holiness, p52). One might even go as far to suggest that we see this in the ground surrounding the burning bush becoming holy, with Yahweh’s condescension (3:5). However, the question remains unanswered: can we see the burning bush as a picture of God’s gracious nearness to sinful and unholy Hebrews?

Alec Motyer, in his BST commentary on Exodus, spills the most ink in making this link. He writes, “The juxtaposition of the transcendent God in all his holiness and vitality and the ordinary, earthly bush is a powerful metaphor for the indwelling, transforming presence of God with his people” (p56). I like that Motyer sees God’s holy presence as transformative. But I am unconvinced that is the purpose of this theophany. In p51-56 Motyer vividly unpacks the burning bush: fire affirms wrath, but outreaching mercy is supremely displayed; without abandoning his divine essence God is able to accommodate himself to the company of sinners; the fire is his holy presence and the smoke serves as a veil for that holiness. We want that to be the meaning, because that theological interpretation comes standard with application for preaching. But I wonder if our theological categories at this point are not overshadowing the literary context.

Motyer offers a second way of understanding the burning bush which – in my opinion – does justice to what is going in at the narrative and what Yahweh is about to reveal about himself to Moses: “I AM WHO I AM” (3:14-15). Moses encounters a fire nourished by its own life, a truly living flame that needs nothing outside of itself to burn. Motyer writes, “The essence of this revelation is that Yahweh is the living God, a self-maintaining, self-sufficient reality that does not need to draw vitality from outside” (p56). This surely makes more sense given the context. So God is not as much revealing his holiness as he is demonstrating his glorious self-existence, independent eternality. When we begin to appropriate this truth we are not struck by God’s condescension; we are moved to awe and assurance by his underived and completely independent power over what he has made, his true divinity.

Motyer offers a second way of understanding the burning bush which – in my opinion – does justice to what is going in at the narrative and what Yahweh is about to reveal about himself to Moses: “I AM WHO I AM” (3:14-15). Moses encounters a fire nourished by its own life, a truly living flame that needs nothing outside of itself to burn. Motyer writes, “The essence of this revelation is that Yahweh is the living God, a self-maintaining, self-sufficient reality that does not need to draw vitality from outside” (p56). This surely makes more sense given the context. So God is not as much revealing his holiness as he is demonstrating his glorious self-existence, independent eternality. When we begin to appropriate this truth we are not struck by God’s condescension; we are moved to awe and assurance by his underived and completely independent power over what he has made, his true divinity.